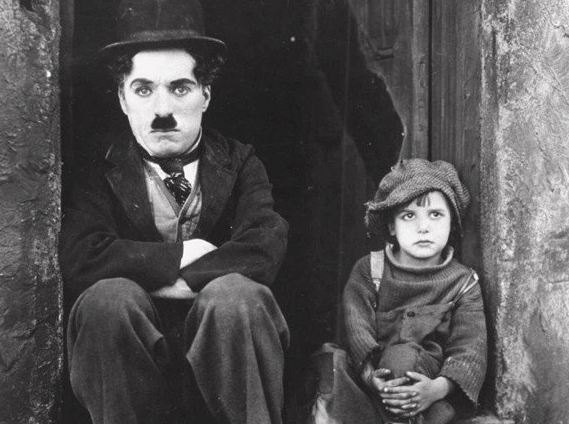

Despite Max Linder (whose films will be reviewed shortly) being the true father of the slapstick silent comedy, Charlie Chaplin is the one to truly take advantage of all of its incredible possibilities on the big screen. He may not have had, at least in his 1921 feature film debut The Kid, the most elaborate gags, but he almost certainly had a gigantic heart that made his films incredibly charming, lovable, and most of all relatable. Using his ever-popular Tramp character that he had developed over the past decade through a variety of short films, Charlie Chaplin decides to take his goofball character with a heart of gold to the big screen. While it may be a small story – a man finds an infant on the street and decides to care for it – the emotions are played up in a big way and the comedy is pure slapstick gold.

Having heard many, many, many things about Chaplin’s films for many years and having never gotten around to them, it was nice to finally make my way into his filmography with such a pleasant start. However, it’s difficult to shake the feeling that the film almost certainly would’ve worked better as a short film. Okay, I get it; a fifty-minute film is already pretty much a short film – especially by today’s standards (where anything under 60 is pretty much declared a short film). That being said, I feel like the first two-thirds of the film are full of wonderful little cutesy moments that draw you in, but the last third (after such a beautifully moving climax involving a rooftop chase scene and what has to be Chaplin at his emotional best) merely lingers until a predictable resolution.

It’s probably unfair to criticize such an early film for predictability, as predictability is something mostly a by-product of living in the 21st century after millions of films have rehashed the same stories for audiences for many decades. Certainly, that’s not what I dislike about the film – which isn’t much I dislike by the way, I still quite love the film – but it’s how it plays out. After such an engaging climax, there’s a lengthy dream sequence that – while funny and light-hearted – does not do much to serve the actual story and feels completely out of place. Once that ends, the film pretty much ends without any heartfelt emotional resolution. It just kind of ends.

At the same time, though, one has to remember this was early cinema and Chaplin’s film was pretty much a breakthrough in terms of blending slapstick comedy and drama together. Perhaps he was still working out the kinks of crafting a feature film and while its last third has flaws, it’s still quite moving and funny – something almost entirely unheard of back in the early 1920s and before (as far as feature films were concerned).

Chaplin perfectly communicates this incredibly heavy and melodramatic story with a fitting light-hearted touch. The two complement each other so well that it’s no wonder the film was such a large hit with audiences back in 1921 (being the second highest grossing film of the year and with a budget less than half of the typical money-makers of the decade). Chaplin, in complete creative control of the product (director, writer, actor, and even composer), uses each of these aspects to deliver on the promise of its opening title card: ”A picture with a smile—and perhaps, a tear.”

Of course, it’s not just Chaplin alone that makes this film work. In what has to be one of the superior child performances, Jackie Coogan does outstanding work as the titular kid. He’s equal parts cute, affecting, and well-coordinated on par with Chaplin’s Tramp. Both he and Chaplin have incredible chemistry that you believe the credibility of their five-year relationship and it only makes the poignant scenes more effective. Edna Purviance also works wonders here as the “woman,” who had given the kid up but soon became a renowned celebrity and charity giver.

While there are undoubtedly many other Chaplin films to explore, this is certainly a film that shows a lot of potential for Chaplin both as a filmmaker, actor, and composer. His biggest strong suit is obviously his care for his audiences, how he wants to offer a story that both makes them smile and cry in equal doses, but he doesn’t play them for fools. He lets plenty of the action in his films speak louder than words, using very minimal dialogue in his films, and the stories hold quite a bit of weight to them. If Keaton was the thrills, then Chaplin was certainly the heart and this film has no shortage of that here.

No comments:

Post a Comment