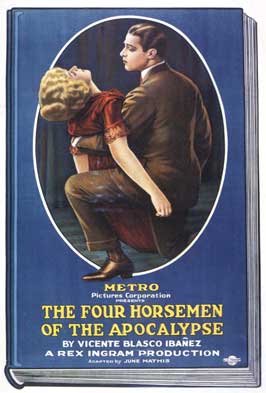

Before Rudolph Valentino rose to stardom in the 1920s, he starred in the lengthy epic on the consequences of war and hatred, Rex Ingram’s The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The film, having very little to do with the actual story of the titular horsemen, plays out similarly to D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in pitting fictional family against family on opposite sides of a real-life war. In this case, the war happens to be the first World War.

Valentino stars as Julio Desnoyers, the reckless grandson of a wealthy Argentinian cattle herder who – despite promising to leave everything to Julio after his death – winds up actually leaving him only half; the other half is given to his German uncle and his three sons who decide to leave home for Germany and continue their education. Julio, on the other hand, decides to go to art school and tango clubs, reveling in days gone by. It’s not until he meets the lovely, but married, Marguerite Laurier (played soulfully by Alice Terry) that he begins to change his ways. To make matters worse, World War I approaches and disrupts his life once more.

Without giving a whole lot away, it’s easy to see why the film managed to be the highest-grossing film of 1921 – even over the likes of Charles Chaplin’s The Kid. Back in the golden days of cinema, audiences yearned for epic stories that swept across time and space – something more than what stood outside their front door. Just as Griffith had excelled at for the past decade, particularly his primary Birth of a Nation, director Rex Ingram and the wonderful screenwriter June Mathis worked together to offer an epic tale of love and hate that not only tied in with the Biblical parable of the Horsemen, but related it to the lives of those affected by World War I.

Perhaps its success was due to World War I being such a fresh aspect of the lives of those in 1921, but nonetheless the film offers plenty in the way of thrills, heart, and passion. From Valentino and Terry’s engaging romance to the destructive and horrific war-time scenarios of which Desnoyers’ father is unfortunately thrown in the midst, the film sets out to do what Birth of a Nation did nearly half a decade earlier, but with much more passion and cutting down the racism (and time, thank God).

Even more brilliant are the performances that layer such a wonderfully knit story. It’s easy to see why Rudolph Valentino (pictured above and to the far right) rose to stardom following this and his other 1921 film, The Sheik’s success. He has charisma for days, especially evident in the first half of the film during his playboy days, but he still has the dramatic chops that perfectly capture the maturity of his character. By his side for most of the latter half is Alice Terry (also above) who shares wonderful chemistry with Valentino, but has plenty of individual moments to shine. She perfectly expresses her character’s internal conflicts while simultaneously making it easy to see why Desnoyers would fall for her in the first place. Outside of those two, Josef Swickard perfectly encapsulates the prideful patriarch (Desnoyers’ father) yet still owns the key dramatic scenes with gusto, and Nigel De Brulier (pictured to the right in the middle, who also did a knock-out turn as the villain in The Three Musketeers the same year) proves quite capable of a noble character as well, playing “the man upstairs” (heh, get it?) from Desnoyers who may or may not be Christ incarnate.

Though the performances make the film feel all the more believable and heartfelt, the film is still Rex Ingram and June Mathis’ all the way. Though the film may seem melodramatic to some – as was custom of the day – Ingram’s fantastic metaphoric use of imagery is startling. In particular, the scene involving the “man upstairs” discussing the Horsemen is a fine piece of filmmaking. Perfectly captures the tone of the beginning of war without ever showing scenes of war whatsoever. But Mathis’ writing, just as she did with the tonally different The Saphead a year before, is what gives the film its wonderful pacing and perfect development. You believe these characters to be real people, that their actions are justified, and that each consequence or reward is earned. It’s a beautiful and epic tale of love and hate, as well as the consequences of war (something All Quiet on the Western Front would make all the more real almost a decade later) that might have set a foundation for many epic tales to come, and showed that Griffith was not the only one who saw something in the idea of cinema’s power – the box office certainly being proof of that. Perhaps filmmakers of today who yearn to weave such intricate epic stories ought to learn a thing or two from the ones who started it all.

_-_1.jpg)

.AVI_snapshot_02.05.51_%5B2015.02.20_12.53.52%5D.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment